9/08/2023

9/07/2023

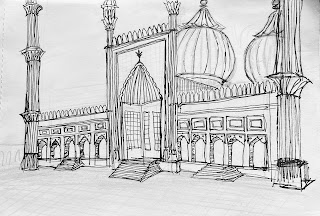

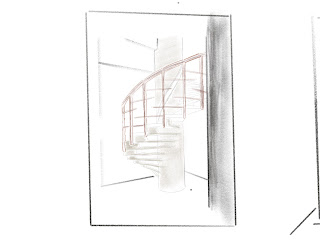

Capturing Architectural Progress: Sharing My Indian Journey Through Drawings

Capturing Architectural Progress: Sharing My Indian Journey Through Drawings

I m publishing my architectural drawings' photos for several reasons, the foremost being to chronicle the progression of my artistic journey. Each drawing is the product of effort, creativity, and personal exploration. By sharing them, I create a visual record of my path, my advancements, and the challenges I have encountered. I've never really drawn before, and this studio is a perfect opportunity to practice this essential skill for an architect.

In exposing my drawings to the scrutiny of others, I also hope to gather constructive feedback and guidance that will aid in my improvement. Architecture is a vast and intricate field, and every drawing represents an opportunity for learning.

Furthermore, sharing creations enables me to connect with a community that shares similar interests. I can exchange ideas, techniques, and inspirations with other artists and architects, fostering an environment conducive to mutual growth.

I will develop later the context and the choice of each draw.

DELHI DERIVE

It allows one to be carried by the wind, sharpening the senses of the one who follows it, compelling them to embrace life's opportunities.

This was an exercise given to us in the city of New Delhi. A 4-hour dérive during the day and 4 hours at night.

An exercise familiar to me as I tend to apply it in my daily life. A guiding thread directs it, but the dérive is a way to bypass the rigidity of a predefined path in society.

It is interesting to disconnect from it for a moment in order to better appreciate it. Often, it offers countless opportunities and encounters.

This day will probably be the only dérive of my life that I will describe in detail.

But it will neither be the first nor, most likely, the last!

Delhi, August 31, 2023.

Our starting point was the Sikh temple Gurudwara Bangla Sahib.

This place, discovered five years ago, had deeply marked me.

It may go against Guy Debord's theory, but being accompanied by two Indians unfamiliar with their own country's other religions, I invited them to meet me there.

10:00 am.

After removing our shoes, a melody called us to climb the marble steps leading to the temple.

Devotees kissed them one by one.

Then a solemn procession followed around a stage where the sung prayer was accompanied by the sharp rhythm of percussion and the resonance of bells.

Around us were carpets with a thousand patterns on which the faithful prayed and meditated.

Then a breeze called us outside, where a sacred pool surrounded by colonnades drew us into their shadows. A narrow strip of 3m/300m provided shelter from the sun and rain for anyone who sought refuge at any hour.

A sanctuary of serenity for those who seek respite, slumber, introspection, or reflection...

A place of communal sharing where one can receive a daily meal without charge.

And even prepare sustenance to offer to the community in the name of God.

We were beckoned by the music and fragrance to proceed at a leisurely pace toward the kitchen, where other women and men, volunteers themselves, extended their warm welcome to us.

Three hundred chapatis were prepared by these souls, accompanied by the temple's music streaming live into the space.

Then came the time for farewells, and also a mild tendinitis...

It was too early to taste our chapatis.

The queue grew in front of the dining hall, and we decided to continue following the melody.

The temple's music called us back to it.

After being drawn in twice by the meanders of this place, repeatedly passing through the same areas, a scent beckoned us toward a dark opening beneath the colonnades' path. It was then that behind this unwelcoming entrance, a small courtyard offered meals at any hour. A simpler fare than that of the main kitchen, yet of quality.

Out of modesty and respect, no photos were taken without the consent of those who might appear in them.

After sharing this meal with strangers, we wondered what adventures were still to come. The scorching heat led us to opt for the northwest direction, where the city's shadow would provide us protection.

We were captivated by an ultra-brutalist, even futuristic building and the precision of its concrete formwork.

Once we resumed our walk, a bus came to a halt before us, its doors wide open, inviting us into its embrace. As we stepped on board, we were greeted by new souls, their faces filled with warmth, who directed us toward a local market that was a vivid tapestry of colors and life. We meandered through the market's labyrinthine alleyways, drawn into shops adorned with saris of a thousand hues, each one telling a story of its own.

That marked the end of the first four hours, but my dérive continued, weaving through a tapestry of experiences and encounters that would remain unrecorded in this narrative, yet they constituted the essence of my day.

19:30 pm.

My dear Indian friends were familiar with Delhi at night as I was, which is to say, quite unfamiliar indeed. In a moment of inspiration, a technique from my Paris life crossed my mind. Forty minutes later, we found ourselves standing inside a theater, its ornate façade illuminated by the soft glow of evening, without ever having to reach for our wallets.

Inside, a captivating performance awaited us—a showcase of traditional dances from various Indian states. For two hours, we wandered within the theater's dimly lit expanse, searching for the perfect vantage point, one that would offer us an unobstructed view of the stage and the vibrant costumes adorning the dancers.

When the curtain fell, we waited with bated breath. As it rose again, it unveiled all the dancers, a riot of color and movement, each figure telling a story through their intricate motions and their thousands colours.

A man two seats away from us extended his phone towards us, inviting us to capture the gratitude. After 30 minutes of video recording, he invited us to explore the theater's backstage and handed us his business card. He turned out to be the director of the Visual and Musical Culture Foundation of Odissi State.

Compelled to venture out, we found ourselves in an art gallery. We had the fortune of catching the final moments of an exhibition blending tradition and poetry. The works on display were explained to us by their creator, Subrata Ghosh, unveiling their essence and depth.

It was then that we realized we were within the confines of Joseph Allen Stein's India Habitat Centre.

The India Habitat Centre stands as one of India's most comprehensive conference venues. Its mission is to bring together individuals and institutions engaged in various fields related to habitat and the environment. Comprised of five blocks interconnected by elevated walkways, we strolled through its spaces, bringing our dérive to a graceful conclusion.

These carefully orchestrated experiences have allowed us to realize that the dérive can be influenced by architecture, and that a space can compel us to never leave its embrace. The drift unfolds through space, climate, the people we encounter, and their culture.

These beautiful and enriching experiences are ones I always delight in repeating.

This experience serves as a reminder that every space, every encounter, and every culture can offer us fresh and enriching perspectives. It teaches us that the dérive, when guided by curiosity and an open mind, can become an extraordinary means of understanding the world that surrounds us.

8/28/2023

Cancel Concrete!

It was only yesterday when we praised and hailed the architecture of exposed concrete: we enjoyed quoting Le Corbusier who said that “The business of Architecture is to establish emotional relationships by means of raw materials" or Alison and Peter Smithson who thought that the concrete architecture "drags a rough poetry out of the confused and powerful forces that are at work." We melted when Rami Karmi shared with us phraseologies such as "The concrete is a material full of darkness".

We were impressed by the honesty of concrete, we believed that it is always a "Truthful, honest negative of the formwork to which it was molded"; we endlessly philosophized about the ethics of the aesthetics and the aesthetics of the ethics; we attributed to concrete qualities and values, "not only honesty, directness and righteousness but also dryness, aggressiveness and imperviousness". We contemplated those concrete structures as if they were philosopher stones that have something to tell us. We wrote that "they expressed what we wanted to be, the way we wanted to see ourselves and what we were demanded to be: bare, real, direct, strong, and above all - irreversible."

Some of us made the pilgrimage to Marseille, Chandigarh, Tokyo or Brasilia to see their grey wonders with their very own eyes. Those who couldn't make the trip could have easily found their wish in Beer-Sheva, Qiryat-Gat, Ein-Guedi, Nazrat-Illit or even in Tel Aviv. We wrote articles, essays and books, we organized exhibitions, symposiums, seminars, tours. We signed petitions and protested against damages that might be caused to brutalist masterpieces, we published fiery articles whenever someone dared to paint them or worse to whitewash them. Some of us even wrote or promoted official plans that assured the preservation of those concrete structure forever. Sometimes we even erected such concrete structures for us and our families.

It is needless to say: today Béton is bon-ton.

All this might have happened even without all this fuss and even without bothering much about concrete's bare appearances. Concrete is today not only bon-ton but above all the most common building material, its use is widespread all over the planet. And even when we don't really see it we know that it is there, somewhere under the ground, behind the claddings or the plasters. We cannot think of our planet's surface without reinforced concrete, this new "Artificial Stone" that turned into the new earth's geological layer. We are addicted to concrete. We cannot do without it.

But let us listen to the German philosopher Anselm Jappe who argues in a recent book that concrete is the "mass construction weapon of capitalism" and that its past and future damages could pare only those caused by capitalism's two other "flag-materials", plastic and oil.

Jappe brings up few important points: Almost in all the countries in the world, concrete is a product of a dubious chain of production in which from one side there is a state-owned or controlled monopolies that are responsible for the quarrying, importation and the production of the cement while the quarrying and supplies of the sand are always handled by organised crime monopolies. And even though in most countries of the world sand quarries are illegal, none of those regulations diminishes the use of concrete, on the contrary. Same goes with all the direct and indirect damages caused by this industry which is usually not taken accountable for its impact - the production of cement itself is extremely polluting.

The concrete production and supplies chains are completed by those of the architecture and the construction. This universal technology, this absolute abstraction of a material that could be easily transported in a form of powder but could easily be solidified into the form of a dam, this Unbearable Lightness of the architect who can sit in his office, imagine a wall and draw a double 0.5 line, or that of the engineer or computer program to calculate it - all these are part of a broader regime. This division of tasks is what enables the industrialization of the planning and the construction process. Concrete is transforming our cities into markets and our homes into financial products, and by the way it transports materials, tools and people from one place in the world to another. Concrete has brought not less than a social revolution that created all over the planet few new billionaires and many new classes of enslaved immigrant workers. If in the past, building sites were places of craftsmanship, creativity and expertise bringing artists and artisans together, today those places have become alienated, sometimes deadly spaces of exploitation and abuse, bulling and lawlessness.

Since the first half of the 20th century, when it started to be massively used, and in few years, concrete eliminated the use of local materials and led to the extinction of centuries-long construction traditions and technologies. In that it had a major role in transforming the whole world into one concrete country in which the differences between places or cities disappear. The result is equally alienated and sometimes ugly in every place on earth.

But above all: reinforced concrete is the newest construction material. It is in use for a century only. Nobody can really tell if this combination of cement, aggregates, steel and water can hold for centuries and what would really happen during the prolonged encounter of those materials with the sun, the water, the air, during the general movement of things towards the unavoidable entropy.

According to Jappe, his main motive in writing this book was the collapse of the Morandi bridge in Genoa in 2018,half a century after its completion. This collapse of this bridge, which had been a major circulation artery of the city, caused the death of 53 people, the injuries of dozens and paralyzed the whole city for a long period of time. The failure of the bridge was due to corrosion that attacked the still cables in its prestressed beams. At the time of its construction, in the 1960s, the Morandi bridge was considered as a technological achievement, but still, it did not last more than half a century. In smaller scales and in much more mundane uses we can see very often typical failures associated with concrete. In many cases they are caused by the unreliable chain of production which enables using unqualified workers and occasional groups. But even when the execution is correct there are quite many known pathologies - capillary cracks, leaks, poor thermic and acoustic performances and gradually, with the material fatigue, we witness crumbling, corrosion, exposure of the steel to air and water and finally, from time to time, columns crack, ceilings collapse, balconies fall. Last year, in the city of Holon, a whole apartment building collapsed. Just like that, because of the light, the air, the utopia.

We must admit that though it has been a default option of almost any architecture of our time, at the moment we do not know how to make concrete last. We can no more say that it is too early to tell if concrete would last forever. We already know it will not. And in the meanwhile, not only we don't actually know how to preserve it when it is really needed, we also don't know what to with it when it becomes obsolete. Briefly we can say that we are not so sure that all this concrete that we have been pouring in the last century would hold for one more century (it is quite likely it will not). We know already that most of what we have built would be either demolished intentionally or collapse spontaneously, but that we do not know what to do with the debris.

5/12/2015

SABA Spring 2014 OccupyTLV in the Mobile Home Project catalogue

Mobile Home Project exhibition - http://mobilehomeproject.com/

SABA's portfolio at the exhibition's website - http://mobilehomeproject.com/?portfolio=saba)